2023 turned out to be another excellent year of reading, where quality trumped quantity, and I’m so glad I chose my books well.

I read more translated literature this year as planned of which 9 translated works made the cut covering 6 languages (German, Spanish, French, Italian, Icelandic, and Japanese). Again, I’ve read more women authors this year, and this is reflected in the list as well (women to men ratio is 17:3). Publishers in the spotlight include McNally Editions, NYRB Classics, Daunt Books Publishing, Virago, Vintage, Pushkin Press, Charco Press, Boiler House Press (Recovered Books imprint), Faber Editions, and Counterpoint.

One of the highlights of 2023 was the year-long reading project – #NYRBWomen23 – hosted by the lovely Kim McNeill on Twitter and other social media platforms. I intend to write more about this in an upcoming piece (given the gems I’ve discovered thanks to this readalong, it deserves a blog post of its own!).

Other readalongs I participated in were as follows – Novellas in November; WIT Month in August; Reading Ireland Month in March; #ReadIndies in February; January in Japan, #NordicFINDS23, and A Year with William Trevor, all in January.

Coming back to this list of 20 books; it is a mix of 20th century literature, contemporary fiction, translated literature, novellas, short stories, diaries, and an imagined memoir. I simply loved them all and would heartily recommend each one.

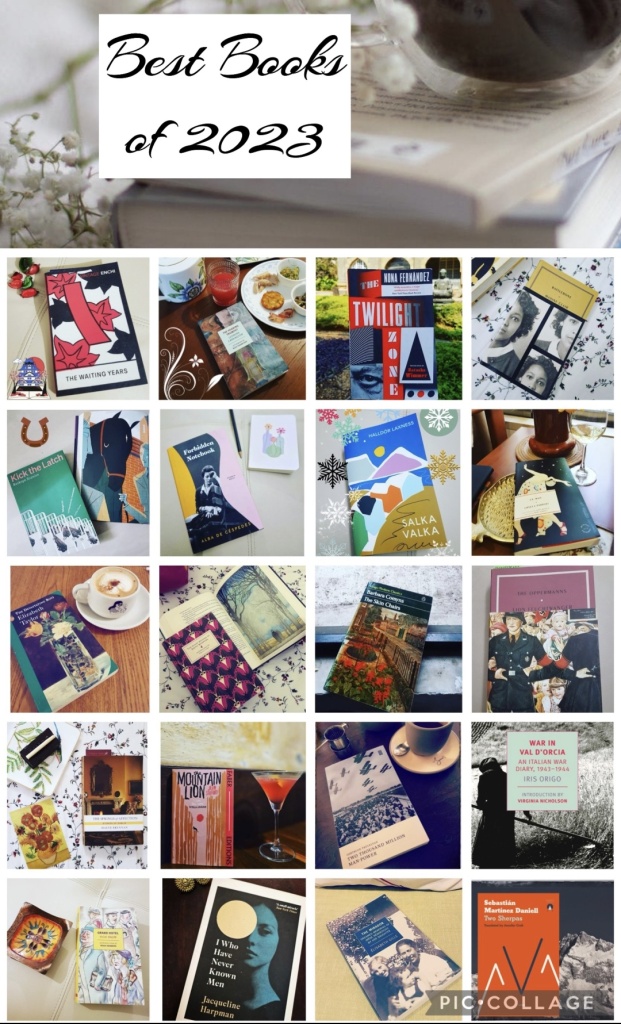

So without further ado, here are My Best Books of 2023 in the order in which they appear in the picture below (from top to bottom and then to the right). For detailed reviews on each, click on the title links…

TWO SHERPAS by Sebastián Martínez Daniell (Translated from Spanish by Jennifer Croft)

In the beginning, two Sherpas peer over the edge of a precipice staring at the depths below where a British climber lies sprawled among the rocks. Almost near the top of Mount Everest, the silence around them is intense, punctuated by the noise of the gushing wind (“If the deafening noise of the wind raveling over the ridges of the Himalayas can be considered silence”). Wishing to emulate the feat of many others before him, the Englishman had aimed to ascend the summit but that ambition now is clearly in disarray. Assisting him in the climb are two Sherpas, one a young man, the other much older, but with this sudden accident, the Sherpas are in a quandary on how to best respond.

Thus, in a span of barely ten to fifteen minutes and using this particular moment as a central story arc, the novel brilliantly spins in different directions in a vortex of themes and ideas that encompass the mystery of the majestic Mount Everest, its significance in the history of imperialist Britain, the ambition of explorers to ascend its summit, attitudes of foreigners towards the Sherpa community to Shakespeare, Julius Caesar and Rome. This is a brilliant, vividly imagined, richly layered novel that gives the reader much to ponder and think about.

TWO THOUSAND MILLION MAN-POWER by Gertrude Trevelyan

Two Thousand Million Man-Power is a brilliant, psychologically astute tale of a marriage with its trials and tribulations, the indignity of unemployment, and the wretchedness of poverty…in a seamless blend of the personal with the global.

The book centres on the relationship and subsequent marriage of Robert Thomas, a scientist at a cosmetics firm, and Katherine Bott, a teacher at a council school; both idealists who believe in progress and prosperity. As they marry, they enjoy a brief period of comfortable suburban living only to be followed by crippling poverty when Robert loses his job. Interwoven with Robert and Katherine’s lives and peppered throughout the novel are snippets of headlines depicting both national and international events. Encompassing a period from the early 1920s to a couple of years before the advent of the Second World War, Robert and Katherine’s relationship is placed in a wider context of astonishing technological advancements but also disturbing political developments. It’s this placing of the personal against a broader economic and political landscape that makes the novel unique and remarkable.

THE MOUNTAIN LION by Jean Stafford

Jean Stafford’s The Mountain Lion is a wonderfully strange and unsettling novel about the trials of adolescence, tumultuous sibling relationships, isolation, alienation, and the alluring enigma of nature.

Ralph and Molly Fawcett, the novel’s pre-adolescent protagonists, reside in Covina, Los Angeles with their mother and their two elder sisters Leah and Rachel. That they are unlike the rest of the family is evident from the striking first chapter itself where we learn of Ralph and Molly’s tendency to get unexpected nosebleeds, the result of having suffered from scarlet fever. These nosebleeds often make them objects of ridicule, and they withdraw into their private interior world, but this shared affliction also forges a special bond between brother and sister. Once their beloved grandfather, Grandpa Kenyon, dies while on his annual visit to the Fawcetts, Ralph and Molly begin to spend the summers at his son Uncle Claude’s ranch in Colorado. For a few years, Ralph and Molly lead a double life flitting between Covina and Colorado, until a decision made by Mrs Fawcett to first travel the world with Leah and Rachel and then relocate with all her children to Connecticut, sets the stage for events to follow complete with the novel’s devastating conclusion.

Stafford’s writing pulsates with a dreamlike, cinematic quality evident in the way she depicts the interiority of her characters, particularly children when pitted against grown-ups, the intensity of emotions playing out against a mesmeric, unsettling, and sinister landscape; potent ingredients that make for an immersive reading experience.

GRAND HOTEL by Vicki Baum (Translated from German by Basil Creighton)

Grand Hotel is a resounding triumph, in which by focusing the spotlight on five core characters from varied walks of life brought together by fate, Baum dwells on their internal dramas as well as their interactions; these are tragic, haunting characters grappling with their inner demons and insecurities while also wrestling with some of the bigger existential questions. The novel sizzles with a vivid sense of place (1920s Berlin) and the language is wonderfully tonal and visual. Also, Baum has a striking way with words that capture the essence of her characters in a few sentences.

THE MIRADOR: DREAMED MEMORIES OF IRÈNE NÉMIROVSKY BY HER DAUGHTER by Élisabeth Gille (Translated from French by Marina Harss)

The Mirador is no ordinary biography. The byline below the title reads “Dreamed Memories of Irène Némirovsky by her Daughter” which is to say Gille has breathed life into her mother by giving her a voice and thus positioned this as a memoir. What we read, therefore, is a first-person narrative giving the impression that it is Irène herself who is speaking directly to us.

The Mirador comprises two sections – the first is Némirovsky’s imagined memoir penned in 1929 covering her childhood in Russia and Paris amid sweeping changes and a rapidly evolving political landscape; while the somber and hauntingly sad second section fast forwards to 1942, days before her arrest at a time when she was living in precarious circumstances with her husband and two young daughters in a small French village, isolated with a deep sense of foreboding with regards the future.

Élisabeth Gille traverses the zenith and nadir of her mother’s glittering but cruelly short life; The Mirador is not only a brilliant, immersive, and deeply humane account of Irène Némirovsky’s life lived in tumultuous Russia and France, but also a window into her legacy and fame as a writer par excellence.

THE HEARING TRUMPET by Leonora Carrington

If you thought a story centred on a 92-year-old protagonist was bound to be dull and depressing, think again. Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet is a delicious romp, a stunning feat of the imagination, and an iconoclastic book if you will that refuses to be pigeonholed into convenient definitions and genres; and in Marian Leatherby, the nonagenarian in this superbly off-kilter tale, Carrington has created an unconventional heroine who is charming, feisty and memorable.

The book begins in a quiet, residential neighbourhood on the outskirts of an unnamed Mexican city where Marian Leatherby, our narrator, resides with her son Galahad, his wife Muriel, and their 25-year-old unmarried son Robert. Marian is not welcome in the house and with the aid of a hearing trumpet gifted to her by her charming loquacious friend Carmella who has a penchant for conjuring up unrealistic and improbable schemes and ideas, Marian learns of her family’s plot to park her in an old age home.

The old-age home is unlike anything she had imagined, and Marian soon begins to settle in, gets introduced to her fellow residents, finds herself entangled in various adventures, and is caught up in the fascinating life of an abbess. The Hearing Trumpet could be considered an extension of Carrington’s identity as a Surrealist artist; the novel is a unique montage of styles and genres that resist the laws of conventional narration to brilliant effect. Just superb!

THE TWILIGHT ZONE by Nona Fernández (Translated from Spanish by Natasha Wimmer)

Using the motif of the 1950s popular science fiction/fantasy show The Twilight Zone, Fernández delves into the unimaginable spaces of horror, violence, and murkiness of the cruel Pinochet regime where beatings, torture, and unexplained disappearances disturbingly became a part of the fabric of everyday life.

In March 1984, Andres Morales, a government security services agent, labeled by our narrator as “the man who tortured people” walks into the offices of the “Cauce” magazine and offers his testimony in exchange for safe passage outside the country. After years of imposing torture tactics on Pinochet’s detractors – members of the Communist party, resistance movements, and left-leaning individuals -something inside Morales snaps (“That night I started to dream of rats. Of dark rooms and rats”). Possibly aghast at the monstrosity of the crimes committed, Morales wishes to confess and in the process hopes to be absolved of those horrific acts.

Much of the book highlights crucial moral questions at play, and the fate of the man who tortured people is central to it – Should he be absolved of his crimes because he had a change of heart and now wants to do right? It’s a powerful, unforgettable book about loss, repression, and rebellion where the premise of the TV show is used to brilliant effect – an exploration of that dark dimension where strangeness and terror rule the roost, and is often unfathomable.

KICK THE LATCH by Kathryn Scanlan

Comprising a series of crystal clear, pristine vignettes with eye-catching titles and nuggets of distilled information, Kathryn Scanlan’s Kick the Latch is such a joy to read – a book that brilliantly captures the panorama of a woman’s life on the Midwest racetracks where her sheer grit, fierce determination and unconditional love for horses enables her to make a mark in a tough field largely dominated by men.

Scanlan’s narrative is dexterously crafted, preserving Sonia’s distinctive style of speech (“there’s a particular language you pick up on the track”), a brilliant feat of ventriloquism if you will where Sonia’s engrossing storytelling skills artfully blend with Scanlan’s own style giving the impression of Sonia speaking through Scanlan. Lean and lyrical, the prose in Kick the Latch is stripped down to its bare essentials but it speaks multitudes, a whole way of life conveyed in as little space as possible but with remarkable tenderness and acuity.

THE WAITING YEARS by Fumiko Enchi (Translated from Japanese by John Bester)

Set at the beginning of the Meiji era, The Waiting Years is a beautifully written, poignant tale of womanhood and forced subservience; a nuanced portrayal of a dysfunctional family dictated by the whims of a wayward man.

Tomo, our protagonist, is married to Yukitomo Shirakawa, a publicly respected man holding a position very high up in the government ranks. In the very first chapter, she is sent to Tokyo to find a respectable young girl who will become her husband’s mistress, a terrible and heartbreaking task she is compelled to carry out. As far as themes go, The Waiting Years, then, is an acutely observed portrait of a marriage and a dysfunctional family, the heartrending sense of entrapment felt by its women who don’t have much agency, which is probably representative of Japanese society at that time. Enchi beautifully captures the internal turmoil that rages not just within Tomo but also within Suga, Yukitomo’s mistress. The subject matter might be bleak, but it’s a powerful book with unforgettable characters whose fates will forever be impinged on my mind.

I WHO HAVE NEVER KNOWN MEN by Jacqueline Harpman (Translated from French by Ros Schwartz)

I Who Have Never Known Men by Jacqueline Harpman is a wonderfully strange, surreal novel of entrapment and survival set in a place that may or may not be planet Earth. It’s a bleak but powerful book in the way it explores the concepts of humanity and community when placed against a dystopian backdrop.

The plot of this novel is fairly simple. A group of forty women of all ages lives imprisoned in an underground cage outside which armed guards keep an eye on them continuously. These women have no idea of the catastrophic event that led to their capture and have a vague recollection of the lives they led before imprisonment. The youngest prisoner in this motley group is a young girl, our unnamed narrator, referred to as “child” by the other women. But then one day, an ear-shattering siren goes off. All of a sudden, the guards disappear, vanishing into thin air. Our narrator quickly takes charge, frees the other women, and the group in sheer trepidation climbs up the stairs out into the open, welcoming and embracing their newfound freedom.

But are they really free? This is a beautiful novel, equally devastating and hopeful, and one that sizzles with compassion and humanity as the characters grapple with dwindling hopes and mounting fear, frustrated by the illusion of freedom that gives them a window of optimism but fails to completely transform their lives.

SALKA VALKA by Haldór Laxness (Translated from Icelandic by Philip Roughton)

Salka Valka is a wondrous, 552-paged, ambitious novel; an immersive, brilliant, often harrowing tale of a beleaguered fishing community and the indomitable spirit of a woman who prides on her independence and strives to improve their lot.

In the opening pages of Salka Valka, a coastal steamer stops at the port of a small, remote fishing village called Oseyri. Nobody can envisage a life here, but on that cold, bleak winter’s night, two figures emerge from the steamer – a woman called Sigurlina and her 11-year-old daughter Salvor (Salka Valka). Sigurlina and Salka Valka have made this journey from the North, certain circumstances having driven them away, and while Reykjavik seems to be their final destination, Sigurlina reduced to a state of penury, cannot afford the cost of the trip further. Oseyri, then, becomes her destination for the time being, she hopes to find a job that will help her make enough money to embark on the journey south. However, fate as we shall see has other plans…

Salka Valka is divided into four sections, each section comprising two parts – the first section focuses on Salka’s time in Oseyri as a teenager, and the second section fast forwards to several years when she is a young woman, independent with her own house and a share in a fishing boat. One of the core themes that the novel addresses is the ugly side of abject poverty and the struggles of the working class, and the second half particularly becomes more political as the debate between capitalism and Bolshevism reaches a fever pitch. Epic in scope and ahead of its times, Salka Valka, then, is a simmering cauldron of various delectable ingredients – a coming-of-age tale, a statement on world politics, a strange beguiling love story, and an unforgettable female lead.

THE SKIN CHAIRS by Barbara Comyns

Barbara Comyns’ The Skin Chairs is a marvellous tale of family, abject poverty, and the bewildering, ghoulish world of adults seen through the eyes of a beguiling 10-year-old girl, a story that has all the elements of Comyns’ trademark offbeat worldview.

When the book opens, ten-year-old Frances is sent to stay for a few days with her ‘horsey’ relations, the Lawrences. Growing up in a family of five siblings (Frances has three sisters and two brothers), we learn that the mother often packs them off to various relatives so that she can have some respite and time for herself. However, Frances’ father dies unexpectedly and with this sudden development, the family is plunged into poverty after having led a life of comfort. Despite the subsequent horrors of their existence, Frances’ life is not without incident; she is an inquisitive, affectionate child and makes some unusual friends, and things do take a turn for the better led by a new arrival at the village which sees the fortunes of the family transform, while the holier-than-thou Lawrences finally get their comeuppance.

The Skin Chairs, then, has all the hallmarks of a characteristic Comynsian world – a child or child-like narrator whose unique, distinct voice manages to belie the hopelessness of the circumstances and take some edge off its horrors making the story not just easier to bear but also incredibly compelling. I was lucky to finally find a copy of this novel, it was so incredibly hard to find.

THE DEVASTATING BOYS by Elizabeth Taylor

The Devastating Boys is a gorgeous collection of stories showcasing Elizabeth Taylor’s unmatched talent and remarkable range both in terms of the worlds she creates and her piercing gaze into the hearts and minds of her characters.

The title story in the collection – “The Devastating Boys” – is a subtle and beautifully written story of a marriage, of how doing things out of the ordinary holds the promise of joy and renewal, while “An Excursion to the Source” is a story about a diffident young woman Polly and her overbearing guardian Gwenda and the unexpected circumstances that confront them on a holiday. One of my favourites, “In and Out the Houses”, is a cleverly constructed tale focusing on the petty jealousies of village life complete with the unspoken disappointments and the secret tinge of envy that mark the lives of its inhabitants, while “Flesh” is another superbly crafted story of loneliness and the tragicomedy of middle-aged romance. It’s a collection that shows Taylor at the top of her game where each story is a joy to savour and treasure.

THE GHOST STORIES OF EDITH WHARTON

Edith Wharton’s Ghost Stories is a brilliant collection of eerie, chilling tales where she uses the medium of spectral visions to explore the familiar terrain of her themes that are so central to her New York novels and stories.

The first story “The Lady Maid’s Bell” is a masterclass in narrative tension, a tale of isolation and loneliness, an unhappy marriage, and devotion. One of my favourites in the collection, “Afterward”, is a superb tale of guilt, moral failings, the repercussions of ill-gotten wealth, and women suffering because of the terrible wrongs of their men. “Bewitched” is a suspenseful story of religion and old, primitive folklore set in the icy wastes and the claustrophobic boundaries of a desolate village; while “Mr Jones”, set in an isolated country manor, dwells on the themes of patriarchal control and dominance both real and ghostly.

Besides the ghosts lurking on these pages, the richness and allure of these stories are further accentuated by the complexity of themes lacing them such as moral corruption, greed, domestic strife, control, entrapment, and abuse; themes that typically form the core of her New York stories but also explored in these ghost stories in a singularly innovative way.

THE SPRINGS OF AFFECTION by Maeve Brennan

Maeve Brennan’s The Springs of Affection: Stories of Dublin is a superb collection filled with stunningly crafted stories of unhappy marriages and slices of Dublin life. The book is divided into three sections, and the first section is possibly more cheery of the lot, mostly comprising autobiographical sketches of Brennan’s childhood in Dublin on Ranelagh Road.

The next two sections focus on the Derdon and Bagot families respectively and are some of the finest stories she has written. The Derdon stories are savage and heartbreaking in their depiction of an unhappy marriage; these are six exquisitely crafted stories of loneliness, bitterness, and misunderstandings, encompassing more than forty years of Hubert and Rose Derdon’s married life. Each story unflinchingly examines the nuances of their relationship from different angles and perspectives, always focusing on the growing alienation and resentment between the couple. In terms of tone, the Bagot set of stories is not as fierce as the Derdon bunch but are still beautifully rendered sketches of an unhappy marriage. The highlight of the collection is the last story which also lends the collection its name – an astute, razor-sharp character study, unlike the relative gentleness of the previous Bagot stories.

The stories in The Springs of Affection are quietly devastating, perhaps even bleak, but they are thrilling to read because of the sheer depth of their themes, Brennan’s psychological acuity, and exquisite writing.

EX-WIFE by Ursula Parrott

Encapsulating the heydays of the Jazz Age, Ex-Wife is a wonderful, whip-smart tale of marriage, relationships, freedom, and women’s independence set in 1920s New York.

The book begins with Patricia, our narrator, telling us that her husband left her four years ago making her the ex-wife of the title. Through Patricia’s reminisces, we learn of her marriage to Peter at a very young age, the events leading up to their separation, and how her life pans out thereafter post that tumultuous period. Luckily, Patricia is not completely down and out; she has her job after all, and a new friendship with Lucia, another ex-wife five years older than her. The two women decide to rent an apartment together and thereby Patricia is flung headlong into a world of freedom, endless partying, men, and one-night stands. Slowly and surely, after many hiccups, Peter recedes into the background.

Ursula Parrott’s writing is sassy, wise, and sharp – snappy one-liners, easy camaraderie, and an air of irreverence are abundant and belie some of the darker moments in the book marked by heartaches, tragedies, disappointments, and wistful yearnings. Patricia’s narrative is laced with the wisdom of hindsight and there’s much humour in her retelling as there is poignancy and understated sadness.

RATTLEBONE by Maxine Clair

Maxine Clair’s Rattlebone is a gorgeously written, heartbreaking compilation of eleven interlinked stories that capture slices of life of an African American community in 1950s Kansas City. It sensitively depicts the journey of Irene Wilson our protagonist from when she is eight years old to her last days in high school; she and her friends traverse a particularly rough terrain of tumultuous family life, challenges and heartaches of growing up, and the blight of occasional violence. Irene is often the central feature in each story, at other times she is on the periphery – the points of view sometimes shift and there are stories where the focus zooms on other members of her family or the black neighbourhood of Rattlebone where she resides.

These are beautiful, sharply observed tales with their tender portrayal of characters who display a quiet strength, an inner reserve that compels them to dream big and carry on despite obstacles and hardships.

THE OPPERMANNS by Lion Feuchtwanger (Translated from German by James Cleugh, revisions by Joshua Cohen)

Lion Feuchtwanger’s The Oppermanns is a haunting, powerful story charting the rise and fall of a rich, cultured, liberal German Jew family during the years leading up to and during Hitler’s rise to power. The author takes his time setting up his cast of characters while simultaneously juxtaposing their situation with the broader grim political developments sweeping throughout the country making it an incredibly immersive read right from the very beginning.

The Oppermanns comprise the three brothers – Martin, Edgar, Gustav, and their sister Klara, married to the East European Jew Jaques Lavendel who is an American citizen but chooses to live in Germany. Established in Berlin, the family’s furniture venture is largely run and managed by Martin. Edgar is an eminent and respected doctor with a thriving practice of his own, while Gustav, the eldest brother, is relatively naïve and sentimental; a man of letters, Gustav is absorbed with his world of books and writing a biography on Lessing, fine dining and women, while oblivious and uninterested in matters concerning politics or economics.

As the Nazis come into power, the Oppermanns are shocked by the scale of the country’s moral breakdown while also unable to fathom the precariousness of their existence in this dramatically altered landscape of their homeland. In this volatile situation, the three brothers are faced with a terrible dilemma – should they flee Germany, or should they stay back?

FORBIDDEN NOTEBOOK by Alba de Céspedes (Translated from Italian by Ann Goldstein)

There’s a scene in Forbidden Notebook where Valeria Cossatti, our protagonist and the narrator, is having lunch with her glamorous friend Clara at her place, a penthouse apartment in Rome. Divorced from her husband, Clara is now an independent woman and a successful filmmaker, but by then Valeria’s position has become much more complex. Her outward façade continues to be that of a traditional woman confined to the role of a homemaker and catering to the needs of her husband and two children, but inwardly Valeria has begun to seethe and resist these conventional norms she is expected to adhere to. Clara believes that Valeria has been lucky to achieve all that she wanted by marrying, but by then Valeria and the reader know the reality to be entirely different – Valeria has been experiencing a deep sense of disillusionment, a feeling she is unable to share with Clara.

It is this intense conflict, growing resistance, and the dual nature of her thoughts and emotions that forms the essence of Alba de Céspedes’s Forbidden Notebook – a rich, multilayered novel of domestic dissatisfaction and awakening seen through the prism of a woman’s private diary. Set in 1950s Rome, not only does the book boldly challenge the validity of restrictive, orthodox roles thrust upon women, and the heartaches of motherhood, but it also dwells on writing as a powerful tool for a woman to find her voice and be heard when those closest to her fail to do so.

Billed as a feminist classic, Forbidden Notebook is a masterclass of insight and imagination, brilliant in the way it provides a window into a woman’s interior life, an internal struggle that oscillates between the desire to discover her true self and also keep it hidden.

WAR IN VAL D’ORCIA: AN ITALIAN WAR DIARY 1943-1944 by Iris Origo

Encompassing a period of one year, War in Val D’Orcia covers events between January 1943 and July 1944; an extremely difficult period for war-ravaged Italy fuelled by the intensity of the conflict and utter chaos in its political landscape. The author, Iris Origo, was an Anglo-American married to an Italian, and much before the war the couple bought and revived a derelict stretch of the Val d’Orcia valley in Tuscany and created an estate. At the height of the war, and at great personal risk, the Origos gave food and shelter to partisans, deserters, and refugees.

War in Val D’Orcia is a first-hand account of the complexity of Italy’s position, the politics prevailing at the time, and the difficulty of going about daily life. A compelling narrative laced with heart-stopping tension, these diary entries lose none of their edge even if we as readers already know how events will eventually pan out…the fact is that Iris Origo at the time did not; thus, the potency of the fear and stress felt by the Origos rubs on to the reader as well.

That’s about it, it was a wonderful year of reading for me and I hope it continues in 2024 too. What were some of your best books this year?

Cheers and Merry Christmas,

Radhika (Radz Pandit)