Having read some wonderful books from Archipelago in the past such as Jacques Poulin’s Autumn Rounds, Ida Jessen’s A Change of Time, Hanne Ørstavik’s Love, and Tarjei Vesaas’ The Birds among others, the time felt ripe to read another title from their catalogue by an author completely new to me. Augusto Higa Oshiro was born to immigrants from Okinawa, Japan, and raised in Lima, Peru, and something of this dual identity is reflected in the novel’s central character.

He closed his eyes, in difficult moments his rationality couldn’t do much for him, as instinctive as this rescue device was, it too could turn into a fish bone in the throat, and every thought, every interpretation of his life, sank him further into defeat, into the closing off of paths, into vapid nothingness.

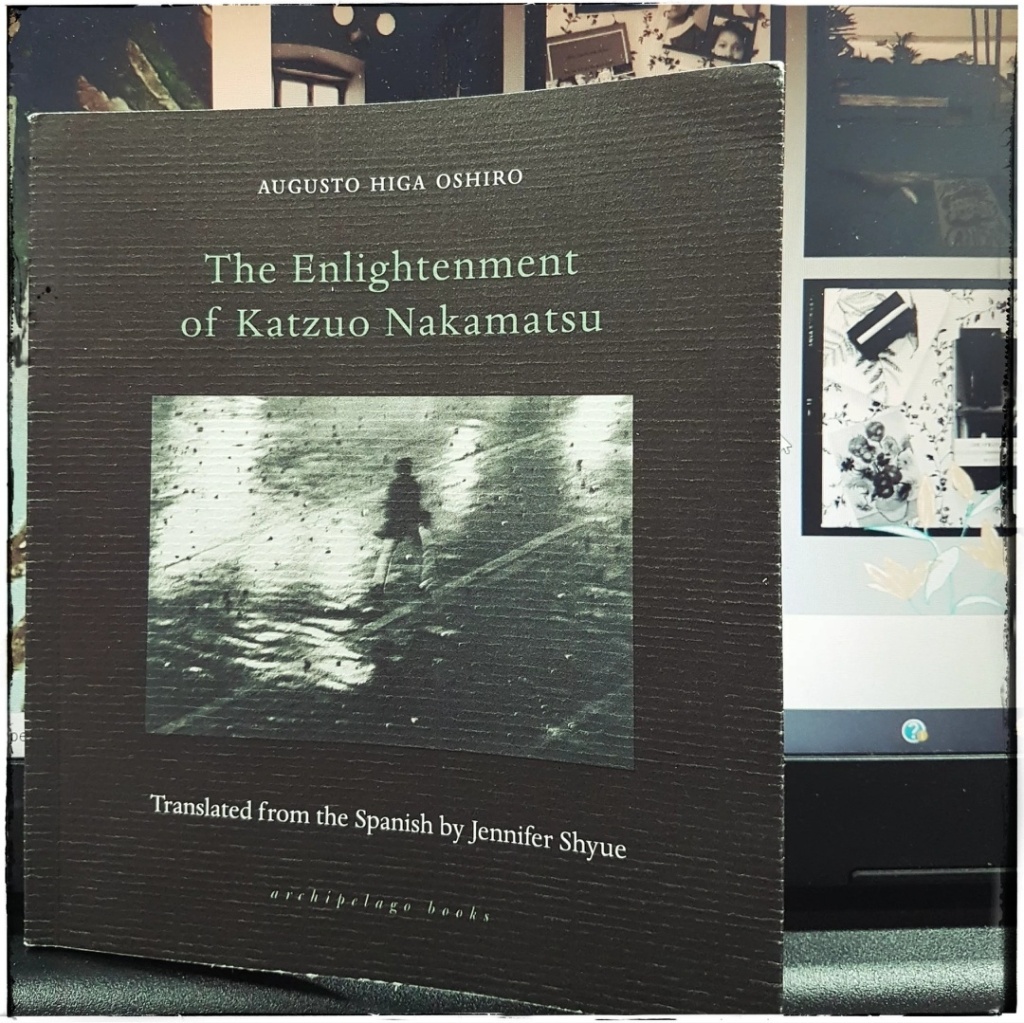

Laden with poetic despair and immersed in a sea of swirling sentences, Augusto Higa Oshiro’s The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu is an elusive, enigmatic, and intense tale of death, madness, isolation, and identity; a brilliant walking novel drenched in dreamlike vibes as it evocatively captures the pulse of Lima, its myriad sights and sounds, making it a deeply haunting reading experience.

We meet Katzuo Nakamatsu on the very first page standing on a pebbled path one August evening mesmerised by the magnificence of the sakura blossoms (“The branches of the small trees, which were scattered around the park and laden with rosy flowers, glowed in the leaden light, filling him with a private joy and, he believed, a secret spirituality”). If this conveys an aura of peace and tranquility, then it proves short-lived, because Katzuo is immediately gripped by an unnamable anguish, “the weight of consciousness, unseeing affliction.”

In the eternity of the instant, in a manner of speaking, the green of the afternoon flickered out, the park’s babbling was erased, as if the world had taken flight, the pebbled paths disappeared, no serene gardens, or laughing families, or murmuring young couples, or ponds full of fish: the only thing in the air now was the sakura tree, its branches and luminous flowers. And in that fragment of afternoon, from that imperturbable beauty, Nakamatsu noticed, sprang a death drive, a vicious feeling, like the sakura were transmitting extinction, a shattering, destruction. Facing this unusual, abnormal reflex, Katzuo managed to close his eyes, as if invaded by exhaustion, it all seemed like a dreadful illusion, abhorrent, and without knowing why he began to tremble, sweating, pallid, shaken to the core, unable to dislodge that feeling of death.

The sight of a festive procession marching down the street with a crew displaying painted faces akin to rag dolls only accentuates Katzuo’s sense of doom and disgust, and sparks a wandering frenzy as he traverses the various neighbourhoods of Lima drinking in their character to calm his clamorous mind.

As the novel progresses, and amid this swirl of dread and fear that waxes and wanes, glimpses of Katzuo’s personality and circumstances emerge. In the present, he is a university professor having embarked on a project to write about the afflicted poet Martín Adán (“a spiritual brother, a twin consciousness in the storm, yes, a man raving at the margins, walled off from the world, majestic and destitute”). We also glean information on Katzuo’s deceased wife Keiko, their life together of which she was the driving force, his siblings and their families, as well as his enterprising, unyielding ancestors, particularly the mysterious Etsuko Untén, his father Zentaró’s best friend, a man whose extraordinary influence over Katzuo will dominate the later pages of this novella.

Katzuo, himself, cuts a solitary figure, a loner with a friend or two (including the one who lends Katzuo his gun), adrift after the death of his wife, who was also his anchor despite their contrasting personalities (“She was an unabashed fighter, a realist, courteous, and then there was Katzuo, the thinker, intellectual, vacillating between the nisei world of his origins and the criollo world, like he belonged to nobody”). His sense of isolation is complete even in the company of his siblings who have all settled well in Lima, integrated into its society with thriving businesses, income, and the comfort of family life. Choosing not to mirror their lives and deliberately veering from the path they’ve taken, Katzuo becomes something of an outsider even to his family let alone his adopted country (“he had always been disposed to austerity, the rigor of ideas and the search for a voice of his own”), a puzzling character they humour out of a sense of duty that forms the crux of Asian culture.

The occasions when he saw them were few, a wedding, wake, an unavoidable celebration, since Katzuo visited nobody, this was his lot, university professor on a meager state salary. The poor relative, unhappy widower, childless, Katzuo lived in a working-class neighborhood in a house inherited from their parents; he felt embarrassment, shame.

One day, on learning that he has been unceremoniously shuttled into retirement, this drastic development comes as a shock, heightening Katzuo’s sense of bewilderment, as he begins toying with the idea of death and suicide.

…he didn’t know how to process the news, it seemed like a joke, retirement, he said or thought, in any case nobody heard him, nor did they see him standing there, unscathed, uncomprehending, with a wounded air and a piece of paper in his hand. Perhaps he silently wept, or muttered curses, either way, Nakamatsu closed his eyes, and felt that his body was being consumed by a flush, an icy fire in his belly. Then everything dissolved into darkness, suffocating circles pricking his head, an increasingly confused haze, warped voices, violent colors, unusual sounds emerging from dreamlike depths.

As Katzuo’s mental landscape spirals out of control (“I have ghosts inside my head”), the novel’s geographic points also shift reflecting his troubled, unraveling mind, and from the majestic vistas of sakura blossoms and the immense splendour of the winter sea, we find ourselves transported to the seamier side of this Peruvian city. The figures of Etsuko Untén and Martín Adán, his ancestor and his research subject respectively, also blend into one another as Katzuo begins to identify with the indomitable spirit and appearance of the former and the physical traits and mannerisms of the latter.

He had discerned that he was to transform himself and dress like Etsuko Untén, that unbridled friend of his father’s, to look the way Untén looked in the photos he kept in the files. And at the same time, this was a means of expressing his recognition of the beloved Martín Adán, and becoming exactly like him, taking on the same reactions, the same gestures, the same gait, the same spirit of estrangement.

Emulating Untén and Adán, and donning a hat and cane with tortoiseshell glasses on his nose, Katzuo begins to traverse the seedy underbelly of Lima – a battery of dive bars, brothels, and other sordid establishments, crime-infested pockets riddled with drug addicts, prostitutes, and unsavoury characters – outwardly showcasing a defiant demeanor, almost as if he is inviting death and violence. Whether this is a deliberate act of self-destruction, or a bizarre calling for salvation or both is hard to tell, but it seems like Katzuo is trying to grasp the essence of his Japanese-Peruvian identity.

And yet, despite all the relentless noise and an all-pervading sense of emptiness and turmoil, Katzuo experiences pockets of tranquility, moments that seem like an oasis of calm and wonder that spring out of nowhere. Quite likely auditory hallucinations, these episodes begin one day in his apartment as he hears birdsong coming from the bedroom, “a concert of chirps and trills emerging bountiful from a recessed grove, with its greenery, flowers, shrubs, and open fields.” A respite then or is this another symptom of his fragile mental state?

Katzuo didn’t make a commotion, he understood that the happening was a result of chance, a fault in the ceiling, a joke or irregularity, in any case, like he was in a bubble, he walked around in his living room, the bedroom, grinding his teeth, hands behind his back, in the kitchen, the taste of virgin earth in his mouth and feral scents on the brain. What at first had been ecstasy and astonishment gradually turned into uncertainty, maybe his mind was playing tricks on him, maybe he was going insane, wasn’t reality itself often incoherent and even absurd?

As the novella unfolds and Katzuo’s feverish nightly odysseys gain pace, remnants of a troubled past and family history begin to emerge from the depths of his consciousness, particularly evolving around Untén, whose aura has left a deep impression on Katzuo fueling his desire to embody him in his quest towards a mystifying form of enlightenment. Themes of the difficulties of immigration and integration come to the fore, disturbingly entwined with the horrific legacy of Japan’s role in the Second World War and the sense of misplaced patriotism imbued in its people, Untén primarily being one of them.

The sense of isolation that Katzuo experiences in his adopted country has its roots in his family history. His father and Untén and their band of people are poor immigrants who settle in Lima but can never assimilate into the fabric of Peruvian society, outcasts perennially ridiculed, jeered, and looked upon suspiciously by the locals. Displaying a peculiar brand of stoicism, these Japanese men soldier on undaunted and undefeated in spirit, developing thick skins impervious to insults and repeated humiliations. Japan’s imperialist ambitions and colonial mindset during the War only alienate Untén’s clan further, although Untén himself remains steadfast in his misguided belief of Japan’s victory.

The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu is replete with an array of sights, sounds, and rich imagery lending the novel a very tonal and visual quality that only enhances its strange beauty. Midway, we see a shift in authorial control – it remains a third-person narrative but it’s like the author has passed on the baton to a new character introduced to take Katzuo’s story forward. The lyrical, labyrinthine, looping sentences not only convey the complex pathways of Katzuo’s disturbed mind but also the contours of the city on his walking jaunts – a place of contrasts alternating between sumptuous gardens, hypnotic beaches, quiet affluent neighbourhoods on one side, and the squalid, forbidden corners depicting degradation and filth on the other.

In a nutshell then, with its themes of alienation and gradual mental disintegration, The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu is a bleak but beautiful novella made compelling by the poetry of its language for which kudos must surely be given to translator Jennifer Shyue.