March and April were hectic months for me – I travelled to Kashmir with family and was also quite busy setting up our new home and getting it ready to shift soon. As a result, my reading and blogging have been a bit patchy – in between bouts of reading consistently, there were days when I didn’t read a single page. But I did read some stellar books during these two months. Of these, two were part of Kim’s #NYRBWomen24 reading project and they were very good, while the rest were a mix of translated literature, short stories, and 20th-century literature written by women.

So, without further ado, here’s a brief look at the nine books…You can read the detailed reviews on the first eight by clicking on the title links, with a review on the Moore to follow soon.

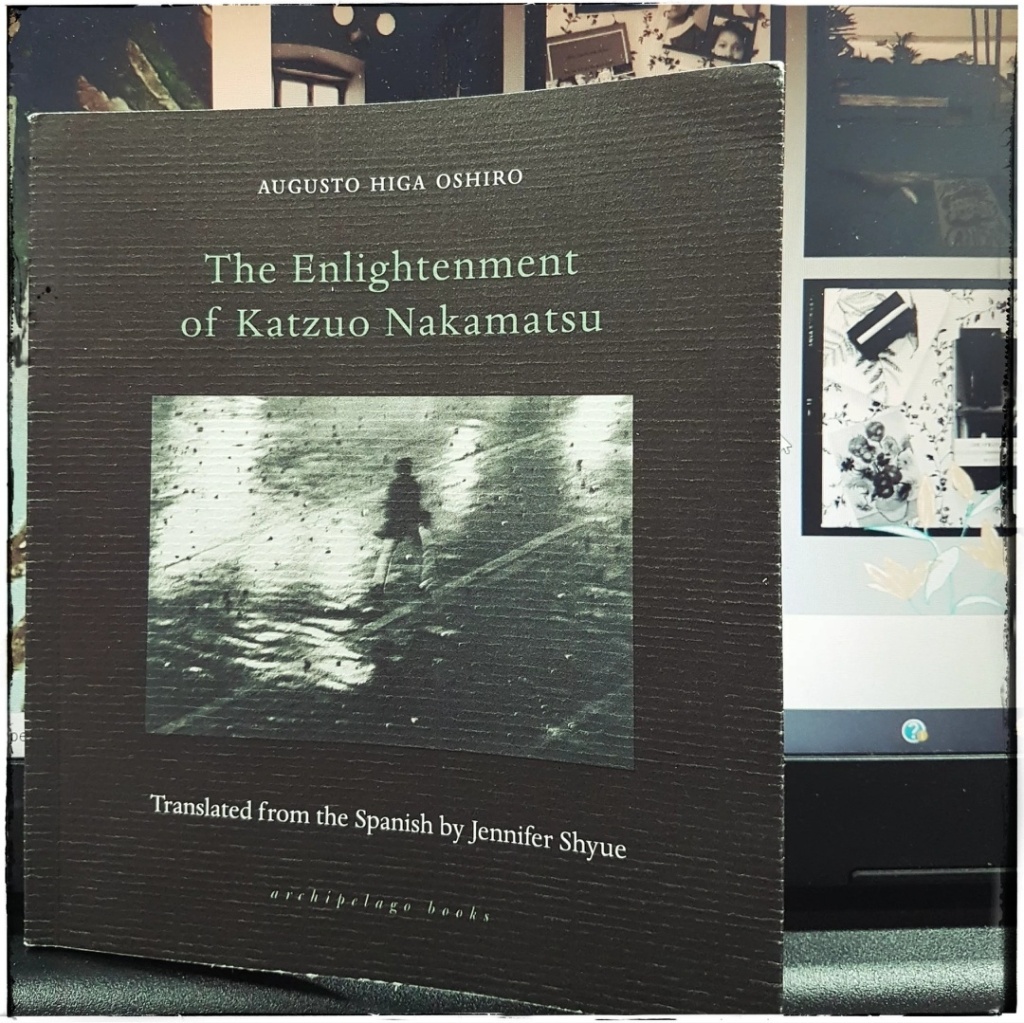

THE ENLIGHTENMENT OF KATZUO NAKAMATSU by Augusto Higa Oshiro (Translated from Spanish by Jennifer Shyue)

Laden with poetic despair and immersed in a sea of swirling sentences, Augusto Higa Oshiro’s The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu is an elusive, enigmatic, and intense tale of death, madness, isolation, and identity; a brilliant walking novel drenched in dreamlike vibes as it evocatively captures the pulse of Lima, its myriad sights and sounds, making it a deeply haunting reading experience.

We meet Katzuo Nakamatsu on the very first page standing on a pebbled path one August evening mesmerised by the magnificence of the sakura blossoms. If this conveys an aura of peace and tranquility, then it proves short-lived, because Katzuo is immediately gripped by an unnamable anguish, “the weight of consciousness, unseeing affliction.”

The Enlightenment of Katzuo Nakamatsu is replete with an array of sights, sounds, and rich imagery lending the novel a very tonal and visual quality that only enhances its strange beauty. The lyrical, labyrinthine, looping sentences not only convey the complex pathways of Katzuo’s disturbed mind but also the contours of the city on his walking jaunts – a place of contrasts alternating between sumptuous gardens, hypnotic beaches, quiet affluent neighbourhoods on one side, and the squalid, forbidden corners depicting degradation and filth on the other.

A CRACK IN THE WALL by Claudia Piñeiro (Translated from Spanish by Miranda France)

I love how Claudia Piñeiro employs the framework of crime to explore relationships and social issues, and in this aspect, A Crack in the Wall is no different; it’s another excellent tale of cowardice, ruthless ambition, moral ambiguity, deception, and precarious relationships.

The novel opens with an image of our protagonist Pablo Simó, sitting at his desk “drawing the outline of a building that will never exist.” Pablo works as an architect in the offices of Borla and Associates, a firm engaged in construction and real estate. Borla, a greedy, ambitious man willing to cut corners, is at the helm of things ably helped by his secretary Marta Horvat (with whom he’s having an affair), a beautiful woman Pablo secretly desires. Pablo has worked for Borla for more than a decade but there’s a sense that both Marta and Borla don’t treat him as an equal, and Pablo seems to have resignedly accepted this. The monotony of his days is not lost on Pablo until a stranger walks into their offices one evening deeply disturbing their fragile sense of calm, and evoking deeply hidden memories of a crime committed in the past. In this novel, Piñeiro’s superb storytelling skills are on full display as she artfully combines the finer elements of plot development with astute character portraits that make for an utterly riveting narrative.

QUARTET IN AUTUMN by Barbara Pym

Quartet in Autumn was Barbara Pym’s penultimate novel published before her death and in terms of tone and subject matter, it’s a different book because of its haunting, sorrowful quality quite unlike her earlier works which displayed her masterful comic flourishes to full effect. And yet it is a lovely, restrained, poignant novel on the heartaches of growing old, deepening loneliness, the sense of emptiness felt post retirement, and unconventional friendships.

We first meet Edwin, Norman, Letty, and Marcia working in a nondescript London office where they are placed in a common room. The nature of their work seems nebulous, we aren’t exactly sure what they do, maybe they are clerks? But this vagueness is deliberate and gives a flavour of the heightened loneliness of these characters particularly when the spectre of retirement begins to flash before them as they are gripped with a feeling of life passing by and a gnawing sense of emptiness. The comedy we are so used to in earlier Pym novels is muted though not absent, and despite its melancholic mood, the ending can be construed as hopeful. I loved it!

A DARK CORNER by Celia Dale

Based on the one Celia Dale novel I’ve read so far (the superb A Helping Hand), I knew that Errol Winston is headed for doom from the opening pages when he lands up one evening on the doorstep of the Didcots, a white, elderly couple. It’s raining cats and dogs, and Errol seems soaked to the skin while also coughing badly. Mrs Didcot, shuffling to the door peers at the paper he thrusts at her, which contains an advertisement for a room on rent. It appears that Errol has made a mistake, and has arrived at the wrong address, there’s certainly no room to let at the Didcots. Errol prepares to leave, but Mrs Didcot takes pity on him, particularly concerned with his hacking cough, and invites him inside to warm himself by the fire, while Mrs Didcot prepares a pot of tea. Deeply exhausted, Errol settles on a chair and falls asleep, and it is during this time that her husband, Arthur Didcot walks in.

In A Dark Corner then, we find ourselves in classic Celia Dale territory, where we are given a glimpse of pure evil that lurks beneath an outward façade of respectability. The overarching premise is pretty similar to A Helping Hand – a couple taking in a lodger in an act of altruism which they believe sets them on high moral ground in the perception of society; how can their kindness be questioned?

KÄSEBIER TAKES BERLIN by Gabriele Tergit (Translated from German by Sophie Duvernoy)

Set in 1920s Berlin, Gabriele Tergit’s Käsebier Takes Berlin, is a lively, zesty satire of the excesses of the period highlighting the power of the press, the transitory nature of the latest news and fads, overhyped personalities, consumerism, and the inevitable downfall fuelled by the Great Depression and the rise of fascism. A novel bursting with a slew of characters, it is difficult really to focus on any one, but the essence of the plot is essentially this:

In the newsroom of Berliner Rundschau, on what has been a slow news week, editor-in-chief Georg Miermann pushes one of his key reporters, a sarcastic man, Emil Gohlisch to publish his article on an upcoming folksy singer. Gohlisch initially haws and hums, but eventually gets his story on Käsebier printed as front page news. Soon, another noted journalist but struggling poet Otto Lambeck writes his piece on a Käsebier show and the breadth of his talent in a rival newspaper, Berliner Tageszaitung, and in the blink of an eye, Käsebier becomes a raging sensation.

In a pace that’s intensely frenetic, Tergit captures the pulse of the period brilliantly in her prose – light and airy, comic and satirical, but also dark and profound. The novel particularly becomes absorbing in the second half when the focus narrows down to certain plot points and is not all over the place.

NOT A RIVER by Selva Almada (Translated from Spanish by Annie McDermott)

Set in a rural region of Argentina, Selva Almada’s Not a River is a brilliant, spare novella about male friendship, trauma, encroaching boundaries, unexpressed guilt, grief, and violence. There’s a cinematic feel to the opening pages as we are presented with the image of Enero Rey standing on the boat in the vast river, poised with a gun. He is not alone, accompanying him is his good friend El Negro and a young kid called Tilo.

The three have come to this island on a camping trip, to spend quality time together, for some much-needed male bonding. Tilo’s father, Eusebio, also a good friend of Enero and El Negro died many years ago, drowned in that very river. On this particular fishing expedition, the three are in pursuit of a large, beautiful sting ray; Enero, dazed by the wine and heat, fires more bullets than is necessary to bring it in. Their activities attract the attention of the island inhabitants – first, a coterie of boys to be followed by a mysterious man called Aguirre, who seems offended by the presence of the three and the manner in which they catch the ray. The sense of tension between the men is immediately palpable, glints of latent menace that fill Enero, El Negro, and Tilo with a sense of foreboding.

Written in a spare, lean style, and impressive in the way it manages to pack the weight of its themes into these slim pages, Not a River is another excellent work by Selva Almada, although The Wind That Lays Waste and Dead Girls remain my favourites.

LAST WORDS FROM MONTMARTRE by Qiu Miaojin (Translated from Chinese by Ari Larissa Heinrich)

Last Words from Montmartre begins on an ominous note signaling the author’s intention to commit suicide, evident not only from the title but also from this epigraph – “For dead little Bunny and Myself, soon dead.” Deeply confessional and an intense, lyrical book about betrayal, heartbreak, passion, breakdown, and death, the novel is structured as a series of letters and diary entries addressed by the unnamed narrator to various lovers, friends, and family members, offering an intimate glimpse into the protagonist’s inner world. Based on the subject matter alone, it is not always an easy read, but the fierce tone and richness of the writing make it pretty compelling.

Qiu Miaojin mysteriously committed suicide after writing Last Words from Montmartre but before its publication fueling discussions about the ‘autobiographical” nature of the novel. This ambiguity is further heightened by these cryptic words at the beginning of the novel – “If this book should be published, readers can begin anywhere. The only connection between the chapters is the time frame in which they were written.” Don’t be fooled by the length – though short, this isn’t a novel that can be breezed through but rather like wine is meant to be sipped slowly and savoured. A book I’m very glad to have read and would recommend!

ONE AFTERNOON by Siân James

One afternoon, our protagonist, Anna accidentally bumps into Charlie, a theatre actor who sweeps her off her feet and the two embark on a whirlwind affair. Anna, we soon learn, is a young widow with three daughters married to Giles who was a Director of the very theatre company which employs Charles and was considerably senior to her. Her daughters, delightfully, welcome this new man in their mother’s life, and while Anna is at first enchanted by his company, soon some insecurities and pangs of jealousy begin to filter in. To make matters complicated, Anna will soon learn of secrets in her deceased husband’s past, of which she had nary a clue, but will change her perception of her marriage and the man she married; factors that will also influence how she views her current relationship with Charlie, and another stodgy man with a tragic air about him who has also taken a fancy to her. This is an intelligent, lovely novel about romantic love, marriage, new relationships, fresh beginnings and finding your feet, and challenging conventional social mores, and the easy, loving relationship between Anna and her three daughters is so beautifully conveyed. The highlight of the book for me was the voice – there’s a charming openness to Anna’s personality as she narrates her story with such refreshing candour. Here’s a quote from the book that I posted on social media…

“However, Giles worked until he’d got everything exactly as he wanted it, including all the furniture. By this time I realise what a marvellous job he did; I’ve never wanted to alter a thing, not even a picture or ornament.

When all the work was finished, he completely lost interest in the house. I could tell that he was surprised by this, but with my vast childhood experience of playing house, I wasn’t at all. The joy was always in planning the rooms, arranging the furniture, finding the right boxes for table and chairs, searching out the kettle, the teapot and the ubiquitous jam jars. Once that was done, the game was deadly dull.”

EASTMOUTH AND OTHER STORIES by Alison Moore

I loved these atmospheric, moody, beautifully written stories. Moore has a flair for unsettling her readers like she did in her superb novels Missing and Death and the Seaside. Again, I plan to put up a review of this collection soon, but here’s a quote from one of her stories called “Seabound” that I posted on Instagram…

“’I’ve spent my whole life here,’ said May.’ All my memories are here. All my things are here.’ She felt at home, in that house on the cliff edge against which the sea beat. Daisy phoned every few days to see how she was, and May said she was fine.

Except sometimes she was troubled in the night. All alone in the big bed that had once belonged to her parents, May dreamt she stood in the shallows at the edge of the sea, which sucked the sand from beneath her feet. She went deeper. Vast and cold, the sea climbed her bare legs. It was rough, but she stood her ground. Sometimes, when she woke from these dreams, the sea was so loud it could have been right there in her room.”

That’s it for March and April. In May, I’ve been reading Life with Picasso by Françoise Gilot as part of #NYRBWomen24 which is excellent so far, the combination of art and memoir is too irresistible and compelling. Plus, I’m also enjoying Lars Gustafsson’s A Tiler’s Afternoon which has a haunting, dreamlike quality to it.